How to get divorced — and keep your fair share of the assets

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

Absence makes the heart grow fonder, as the saying goes, so what happens when couples are forced to spend 24 hours a day, seven days a week with each other for months on end? Add in school closures, questions over childcare and the pressures of work, and even the strongest relationships have been tested over the past few months.

Lawyers say lockdown has raised the financial and emotional strain on couples, prompting a surge in divorce inquiries. Between lockdown being declared in England on March 23 and mid-May, the number of people inquiring about a divorce rose by 42 per cent, according to law firm Co-op Legal Services. In certain weeks of the pandemic, the rise was as high as 75 per cent compared with the previous year.

Mark Harrop, a lawyer at Family Law Partners, says: “From the early stages of lockdown, and on an increasing basis, we have had inquiries from people who have just wanted to understand their position so they can take stock of where they are and plan.”

Couples who were able to live together in normal times — helped by the distractions of work, friends and the ability to leave the home — have been pushed to the limit by the demands of lockdown, with “tensions simmering and often boiling over”, he says.

Enforced time spent together is not the only factor causing problems, says Sarah Coles, personal finance analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown. “Many people are also facing the stress of changing circumstances and in many cases the difficulties of living on a reduced income.”

Negotiating a divorce at times of economic stability is difficult enough. As asset values fluctuate in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, the task of figuring out a fair split is made harder still. Whether you are simply contemplating divorce or have come to the end of the road in your relationship, there are numerous financial and practical aspects to be considered in deciding to untie the knot.

Dividing assets

There is no standard formula for calculating appropriate financial provision on divorce. But Charlotte Coyle, a senior solicitor at law firm Goodman Derrick, says the court has a duty to consider all the circumstances of the case and to take into account a range of specific factors including income, financial resources, needs, standard of living, age and disability.

“The factors are used to determine a fair financial outcome with the starting point usually being that assets accrued during a marriage are divided equally,” says Ms Coyle. She says the guiding principles that apply to reaching a fair financial outcome are “sharing”, “needs” and “compensation”, with “needs” trumping everything.

“The matrimonial home is normally considered a matrimonial asset, even if it was owned by one party before the marriage,” she says.

Splitting assets fairly in the current climate is complicated. Julian Lipson, partner in family law department at Withers, says: “The court will look at the couple’s finances at a particular moment in time. Investments, pensions and properties may well have decreased in value in the current climate and be very different from, say, the start of the year.”

Lawyers and the courts are sensitive to the idea of risk so will often divide things up by percentages, he says. For example, cash from the sale of the family home can be split as a percentage of the sale proceeds rather than a fixed sum of money to ensure both parties share in the upside or downside of the property market.

Covid-19 nonetheless presents both potential challenges and opportunities in terms of valuing and allocating assets between a divorcing couple. The timing of a divorce can produce very different results, particularly for spouses in a financially unequal marriage.

For the financially dominant party, there may be a perceived tactical advantage to push forward with the divorce now, particularly if it is possible to capitalise on lower asset valuations and to benefit after the split from an expected increase in their value. Lois Rogers, director of divorce at law firm Vardags, says: “For others, waiting to see what happens may feel like the better option, for example if a significant business asset has been impacted by Covid-19.”

Extreme volatility in equity markets in recent months has hit dividend income. Hetty Gleave, partner in the family department at Hunters Law, says this may affect pension income or maintenance awards. “Many people have also had pay cuts, so until they know whether this is a temporary or permanent measure, it may be unsafe to discuss longer term maintenance,” says Ms Gleave.

If weighing up assets against one another, their relative values become an issue. “For example, your pension may have dropped in value, while your property is not yet showing a significant fall,” explains Ms Coles. “If you were planning to trade one off against the other, the figures may not add up.”

The problem for many people is that they do not have any way of telling what would happen if they waited. “Your pension could recover and house prices fall — so the pension can be traded more effectively against the house,” says Ms Coles.

“Alternatively, the pension could face further falls and property prices remain robust. Not being able accurately to predict the future makes it impossible to identify the perfect time to start divorce proceedings.”

Splitting a pension

What to do with a pension pot is one of the most complex areas of financial planning in divorce. Although pension pots are often the second most-valuable asset in a split, they are often overlooked. Research by the Pensions Policy Institute published this week found seven out of 10 (71 per cent) divorce settlements did not take pensions into account.

This can leave one party — more often than not, a woman — worse off in retirement. The median pension wealth of a divorced man is £103,500, one-third less than the average man’s (£156,500) but the median pension wealth of a divorced woman is £26,100 – half of the average woman’s savings of £51,000, the research found.

Matt Sullivan, head of professional services at Brewin Dolphin, says: “Statistically, if any party in a financial settlement is more likely to be unfairly treated, it is the wife. For a number of reasons, including time spent being the homemaker, many women tend to invest less in pensions throughout their career.”

Courts currently deal with pension arrangements in three ways. One side could get a percentage share of the former partner’s pension pot, an option called pension sharing; the value of a pension can be offset against other assets, called pension offsetting; or part of one person’s pension can be paid to the other person, known as a pension attachment order.

Mr Sullivan says pension sharing is often the favoured way of dividing a retirement fund because it achieves a “clean break”. This involves couples splitting one or more pensions.

Problems occur most often when there is a mixture of defined benefit and defined contribution pension schemes, or where there is a need to find a fair financial settlement that involves offsetting pension assets with other kinds of assets.

Kate Daly, co-founder of Amicable, an online divorce service, says pension offsetting can produce unpredictable results. “If you are offsetting assets against each other and one asset class has fallen in value more than another, for example a pension has decreased in percentage terms more than the value of your home, then you can find yourself at a disadvantage.”

Most lawyers urge caution on anyone thinking of starting divorce proceedings during a pandemic. Jo Edwards, head of family law at Forsters, says now is not the time for making life-changing decisions.

“My advice is not to make decisions in haste, at what is the most stressful time that many will have ever lived through. Before calling time on your marriage, attend couple’s counselling to try to repair the cracks caused or exacerbated by this exceptional period.”

If a partner is determined to go ahead, bear in mind it is important to get advice regarding the financial aspects of a divorce as early as possible. “This shouldn’t be left to the end of the process,” says Carla Morris, financial planner at wealth manager Brewin Dolphin. “Many people think about the house . . . but overlook savings, investments and pensions.”

She recommends having all of the financial paperwork to hand and ensuring that you have the most up-to-date valuations of your investments and pension policies. This will give you a fullest possible picture of your joint finances.

The impact of Covid-19 on investment performance and savings returns has only added to this argument. “Who is entitled to what may depend on when certain assets were purchased. It’s important to understand what was in place before a couple married and what has been built up together since,” says Ms Morris.

Lockdown troubles

Those embarking on a divorce say one of the hardest parts of the process in recent months has been finding privacy to have those initial conversations with a lawyer.

Those fortunate enough to have second homes or larger properties with outbuildings have been able to take advantage of physical separation rather than having to be stuck under one roof, says Ms Rogers at Vardags. “For many couples, that is simply not possible and more creative solutions need to be found.”

In a single building, zonal arrangements are not uncommon, she says. Partners inhabit different areas of the property and restrict movements between them, defining the times when they may use shared spaces such as the kitchen. This was the case even before lockdown, where neither party would agree to move out of the family home or doing so was unaffordable.

“We have conducted entire new meetings with clients through WhatsApp and have had to be flexible with our availability and more unusual times, while people seize a moment of solitude, whether on their government-mandated walk or late at night,” says Ms Rogers. “One client can only speak to me while pretending she is having a long shower.”

Many legal processes have been on hold during lockdown but not divorce. Divorce petitions were, and continue to be, issued by the courts and anyone can petition for divorce at any time once you have been married for a year. Online divorce petitions are available from the gov.uk website and cost £550. Partners may do it themselves or instruct a solicitor.

Christopher Hames, a barrister at 4PB, says: “While the legal process to end the marriage is quite simple, often the real difficulties arise with disputes about the future care of children and financial issues such as how to divide the family home, business wealth and pensions as well as whether and if so how much maintenance should be paid to your ex-spouse.”

Is it affordable?

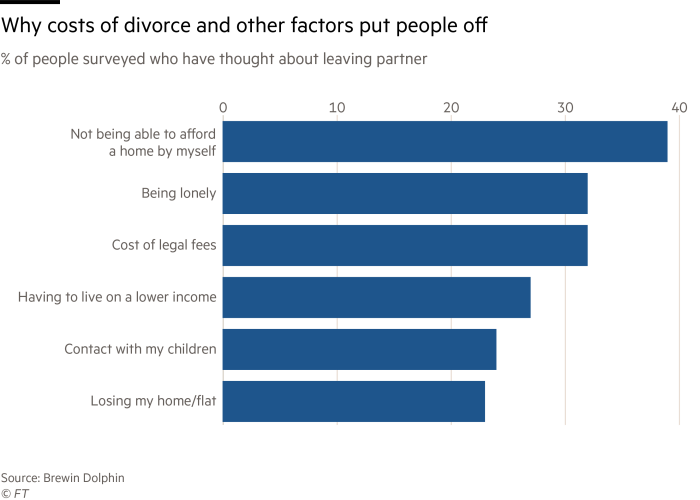

Some people contemplating divorce have been put off by the costs, according to research from Brewin Dolphin. The average divorce costs over £22,000 when taking into account legal fees, the division of assets, child maintenance costs and other costs relating to divorce.

In a survey of over 2,000 adults, 39 per cent of those who said they wanted to leave their spouse said they were worried they would not be able to afford a home on their own.

Ms Morris says: “The cost of legal fees as well as the fear of being unable to afford to live alone, or to live as a single parent, and the uncertainty caused by not knowing how the assets will be split are clearly playing a role in people’s decisions to divorce.” But she makes the point that six months on and faced with the economic aftermath of the global pandemic, the financial position of couples will be even more uncertain.

One of the biggest concerns for most divorcing couples is how they will afford to run two households. Mr Harrop says he encourages clients to discuss their decision sensitively and to use mediation or collaborative negotiations. These encourage couples to work cooperatively, drawing on the expertise of specialists, such as financial advisers and family consultants, to find workable solutions.

“The sad fact is that launching straight into court proceedings can cause acrimony and legal fees to skyrocket. There is nothing more frustrating than when a couple who could have afforded a home each no longer can because they have spent the money on lawyers instead,” says Mr Harrop.

New legislation

One thing set to make divorce easier is the introduction of the Divorce, Dissolution and Separation Act, familiarly known as the “no fault” divorce act, which gained Royal Assent on June 26. This proposes to implement a number of changes to divorce law in England and Wales, most significantly removing the requirement for one spouse to blame the other in order to obtain a divorce.

Jane McDonagh, partner at Simons Muirhead & Burton, says: “Removing the element of blame from the initial part of the divorce process will make it a lot easier for a positive tone to be set for future discussions on more substantive issues such as child arrangements and splitting assets.”

Under the proposed legislation, a husband or wife seeking a divorce will simply need to state to the court that their marriage has broken down “irretrievably” and there is no requirement to prove that statement by submitting evidence.

It is just as well that divorcing couples will soon be able to start their negotiations on a more neutral footing, since the long-term fallout from the coronavirus crisis is only likely to complicate the process of disentanglement.

Challenging maintenance agreements

People who have had their finances hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic are challenging divorce settlements and maintenance payments to ex-partners, say lawyers.

Since lockdown began, courts have been inundated with applications to revisit financial rulings as a result of the payer being unable to keep up with payments or a fall in asset values.

Charlotte Coyle, a senior solicitor at Goodman Derrick, says clients are asking whether they can reopen their case and vary the financial order now their assets have effectively been depleted as a result of the pandemic.

“Since lockdown began, we have also seen an increase in inquiries regarding maintenance payments,” says Ms Coyle. “Most people are worried about their ability to pay and whether they can reduce their maintenance payments.” She says people can ask for these payments to be reviewed or varied by their ex-partner and see if they can reach an agreement to reduce the level of payment being made.

But any changes will need to be done by agreement. If you agreed maintenance between you in the first place, you can agree changes to it too. If the court set maintenance, it will need to approve these changes.

This ability to revisit maintenance is one reason why, when there are sufficient assets, it is often in everyone’s best interests to secure a “clean break”, where maintenance is pulled together in a single lump sum.

Whatever happens, the party paying maintenance should not just stop paying, says Jo Edwards, head of the family team at law firm Forsters. You are under an obligation to pay unless and until you agree, or the court orders otherwise.

“If your situation is so dire that you have no choice but to reduce or stop payments unilaterally, ideally a solicitor should write to your ex explaining why you have had to take those steps, giving broad details of your current financial circumstances and what you see as being the triggers for the previous level of maintenance resuming.”

Comments